Phungni Devi (Fungani Devi), a revered goddess believed to be the sister of Narain, holds a significant place in local traditions. Her temple, located not far from Narain’s home, becomes the centre of mystical rites during a special festival in her honour. Considered a manifestation of Kali, Phungni Devi is also identified with Parmeshri, the great goddess who dwells on a prominent snowy peak that separates Kulu from the Chamha State.

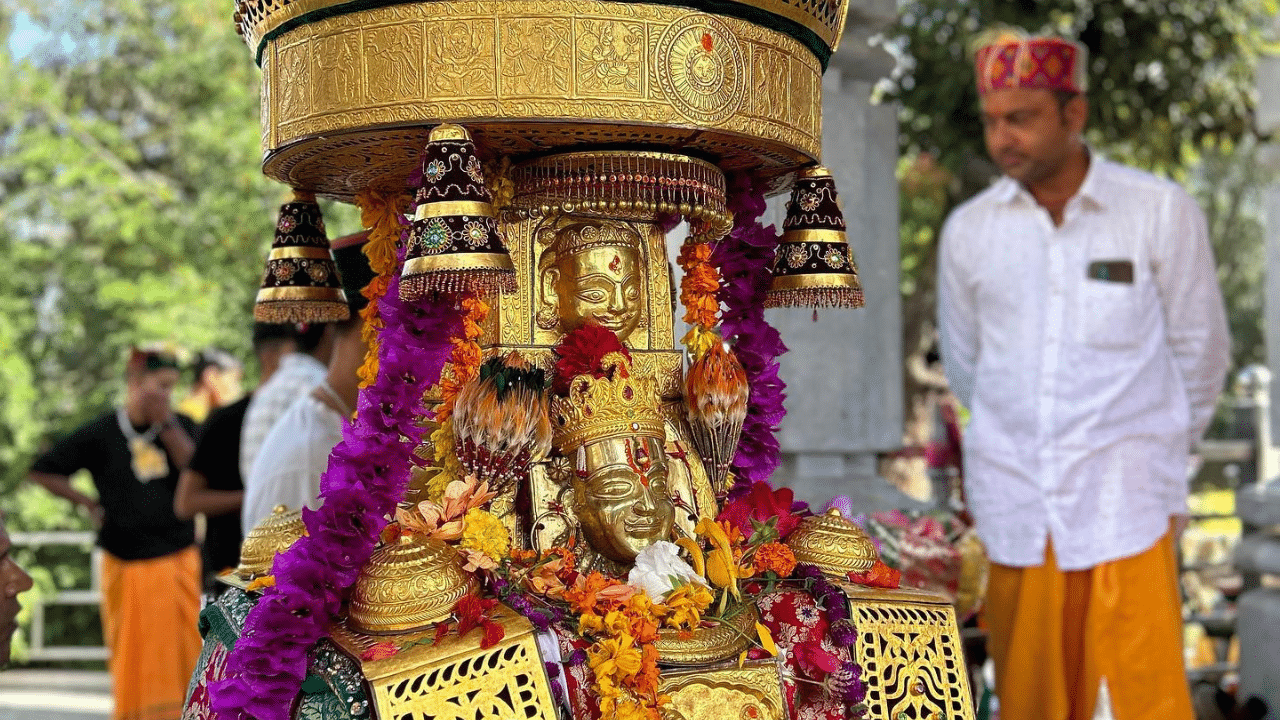

This sacred peak, visible for miles, draws the devotion of the Gujars, nomadic herdsmen who bow in reverence and offer goat sacrifices as they bring their herds to the high pastures for summer grazing. These rituals, steeped in ancient beliefs, form a captivating part of the festival’s ceremonies.

History of Phungni Devi

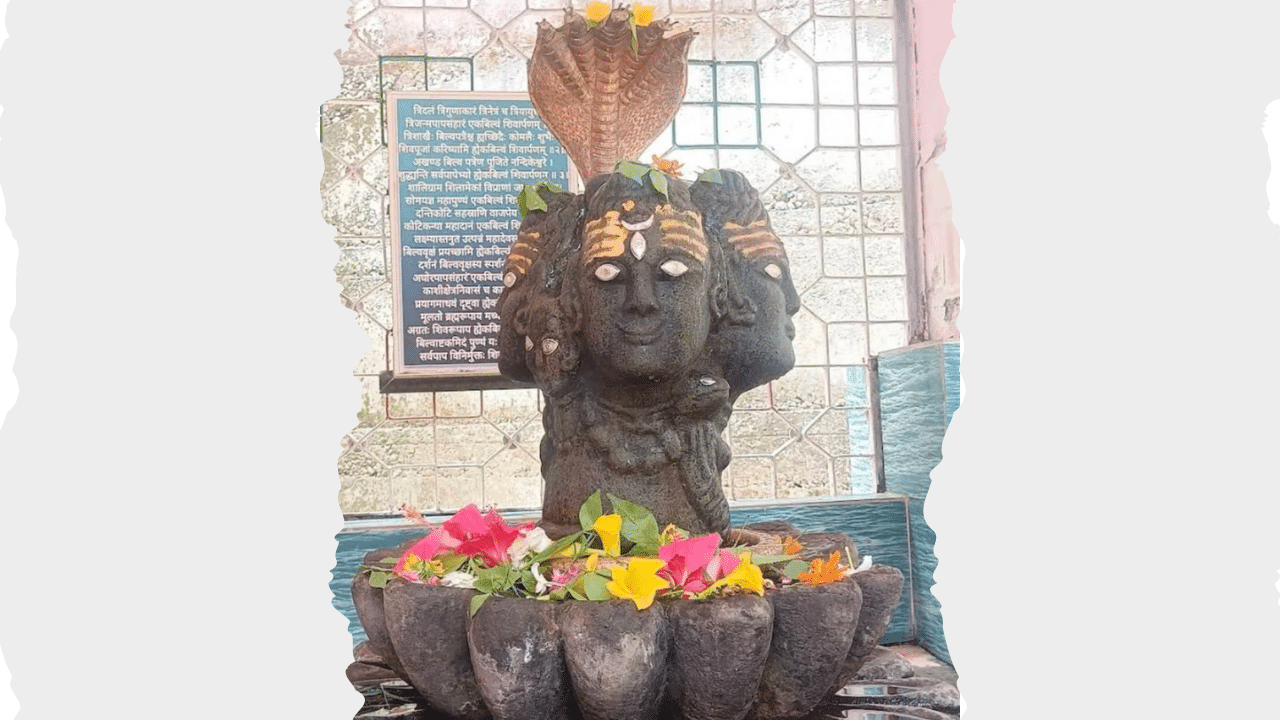

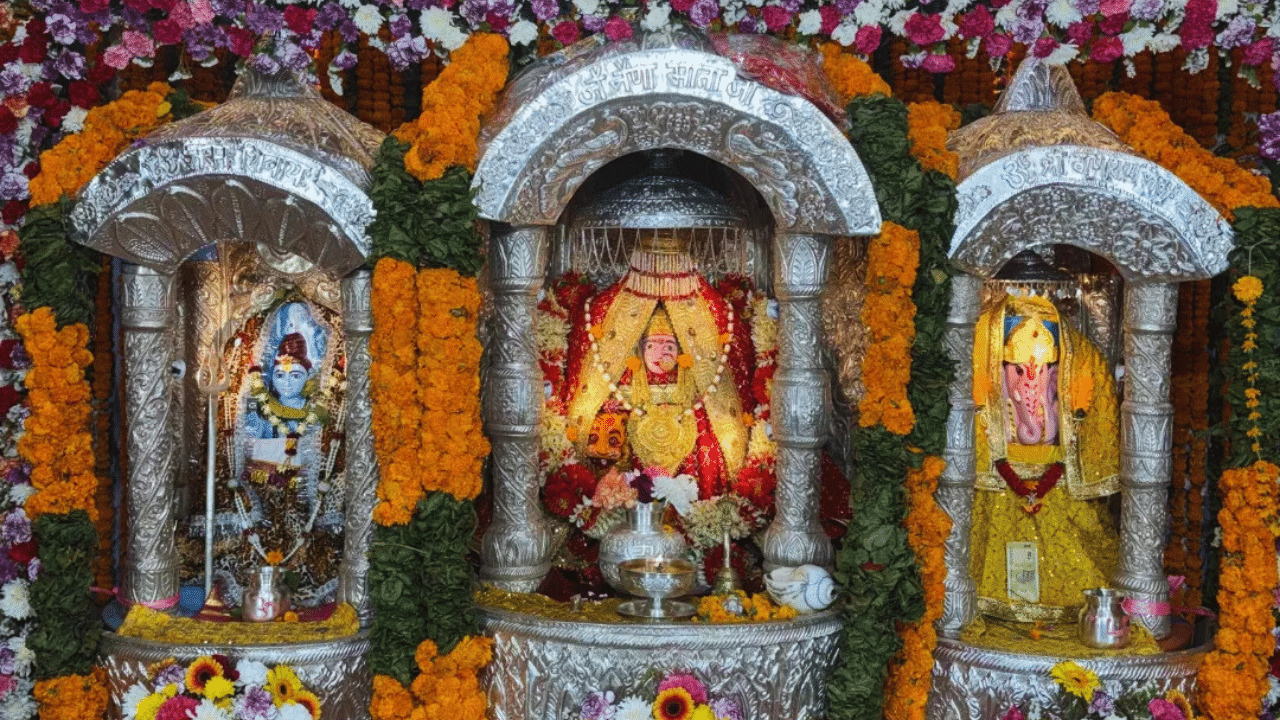

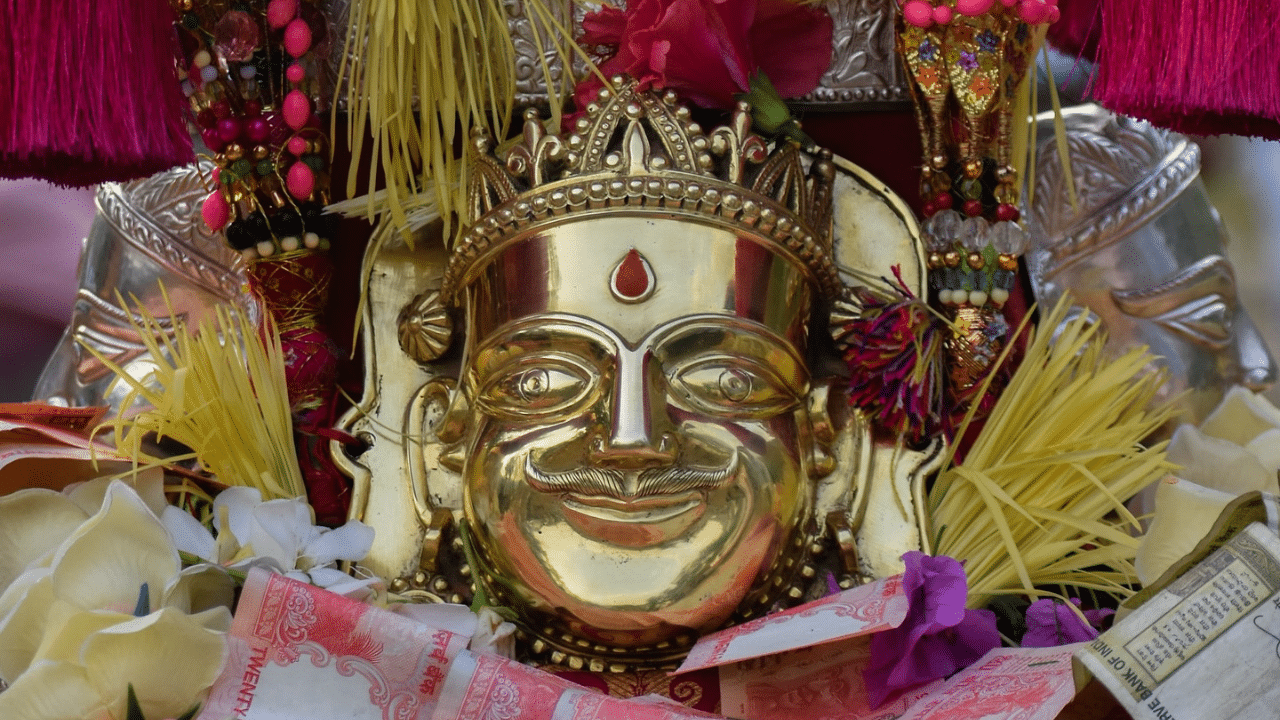

At a similar festival in honour of Phungani Devi ( Fungani Devi )certain mystical rites form a very interesting part of the ceremonies. This goddess has her temple not many miles away from the home of Narain, whose sister she is supposed to be. She is a manifestation of Kali and the people identify her with Parmeshri, the great goddess, one of whose many habitations is on the snowy peak of the same name which stands out pre-eminent in the range of mountains separating Kulu from the Chamha State.

Her home is visible for many miles and the Gujars, the nomadic herdsmen of the hills, pay adoration to her when they bring their herds for the summer grazing to the higher slopes. Looking towards the peak they bow several times and then immolate a goat in her honour.

In Kullu, the word Phungni appears to be another name for the jogni, the hand-maiden of Kali, found on every mountain summit and is used to denote a special form of worship celebrated in her name. The peasants climb to a hilltop, where they sacrifice a goat, sheep or lamb to the jogni, and after worshipping her paint a large flat stone with different colours, laying on it the liver of the slaughtered victim.

The Phungni Devi ( Fungani Devi ) with whom we are concerned is the family deity of the village and is worshipped as the goddess of the Alpine pastures, being entitled in this attribute to the firstborn of the flocks that browse on her preserves. Close to the Mandi-Kulu border, at a high altitude, is a mountain lake sacred to her, The water, so the people say, is as clear as crystal, its surface unbroken even by a twig or blade of grass; for the birds, the servants of the Devi, swoop down to the water and bear away in their beaks the flotsam of the lake.

Her main temple is in a hamlet about 8,000 feet in altitude which nestles with its terraced cultivation amongst forests of blue pine and deodar. Her worshippers are under several restrictions. They may not wear shoes of leather nor smoke tobacco; and even her drummers are men of high caste, no man of low caste being allowed to approach her shrine or litter. Even at the kaika festival, the village menials have to watch the celebrations from the far side of a ravine.

These take place at irregular intervals according to the means of the people. The Nar belongs to the same group of families as supplies the scapegoat at Hurang and comes to the temple with the Narayan, his companion, a few days before the festival begins. He is treated as the guest of the god, being under the same taboos as the Nar of Hurang Narayan, while special preparations are made to create a favourable environment in which he may perform his functions.

Final words

Source: Gazetteer of the Mandi State